Bedeken Ceremony: Jewish Veil Tradition

If you have ever been to a traditional Jewish wedding, probably the most electrifying moment of the evening was the Bedeken, the Jewish wedding veiling ceremony. This Jewish ceremony has its origins in the stories of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs in the book of Genesis.

The bedeken ceremony often spelled badeken, is a Yiddish word that literally means to “check” or “confirm”. An Ashkenazi tradition (minhag), rather than a legal (halachic) ceremony, it takes place immediately before the chuppah. The Sephardic and Mizrachi Jews do not have a Jewish wedding veiling ceremony and the henna ceremony (the Hina) is considered to be the Sephardic counterpart to the bedeken.

The Jewish Veil Tradition

What is the story behind the veil? Like most things in Jewish tradition, there is never one single explanation. Most people believe that the Jewish bride wearing a veil originates with the story of Rebecca, on her first meeting with Isaac, “She took her veil and covered herself” (Gen 24:64). Here, the veil is an allusion to the bride’s modesty.

The Jewish veiling ceremony, itself, is usually traced to the story of Jacob, who is tricked by his father-in-law Laban into marrying the wrong bride Leah, the sister of his beloved Rachel. Jacob’s lesson is noted and in the bedeken ceremony, the bride is seen (confirmed) and veiled by her groom- just minutes before they walk to the chuppah and make their marriage official.

Kabbalists offer another interpretation of the Jewish veil tradition, being that the groom’s love for the bride goes far beyond her physical beauty. The veiling of his bride is viewed as a symbolic act of focusing on the inner beauty and qualities of the woman he is marrying. The veil requires the groom to be reminded that marriage is not only of the physical realm but that of the spiritual, as well.

The Traditional Bridal Reception, Bedeken, and Tish

At an Orthodox Jewish wedding, typically, the bride and groom hold two receptions. While the bride is seated on her bridal throne in one room, the groom is busy holding his groom’s reception called a Tish in a separate room.

Sitting on her bedeken chair, the bride receives her guests, and they, in turn, compliment and entertain her with bedeken songs and dance; in general, they keep her distracted, happy and relaxed.

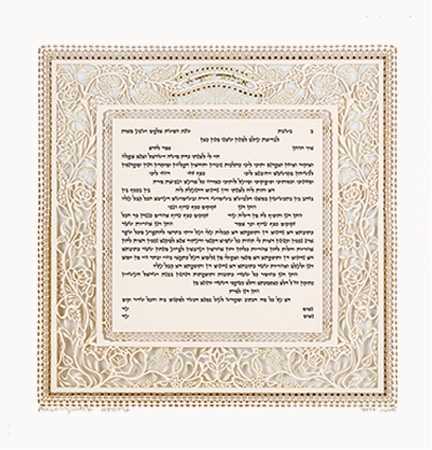

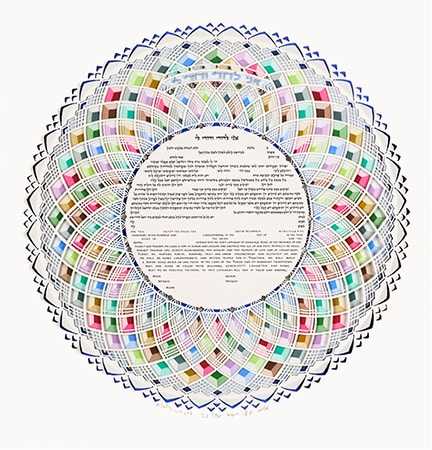

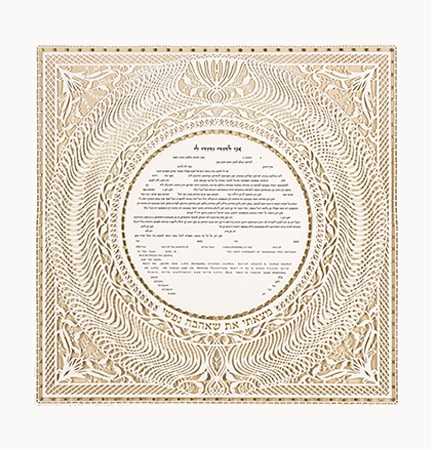

In the meantime, in a different area of the wedding venue, the groom, at his tish or tisch (Yiddish for “table”), is seated with family, friends, and rabbi around a table laid with food, whiskey, and wine. The groom is supposed to give a d’var Torah: an interpretation of the weekly Torah portion. But, not truly expected to have the presence of mind to give a well-thought out talk, he is mostly heckled by his friends and toasted by the participants. The atmosphere is typical, rambunctious, and high-spirited. After this, the ketubah is signed and witnessed by two male (Sabbath observing) witnesses.

With the start of the bedeken music- the Jewish veiling ceremony is signaled to begin. The groom is literally danced and serenaded by his rowdy entourage as he walks towards the bride, views her, and pulls her veil down over her face. For Orthodox couples, who have not seen each other for at least a week this is a highly emotionally -charged moment that leaves quite an impact on the celebrants.

The bride is then blessed with the bedeken blessings:

.“Achoteinu aht hayee l’allfay rehvavah, vahyirash zahrahcha eht she’ar soanav.

“Our sister, may you be the mother of thousands and tens of thousands. And may your children possess the gate of those who hate them.” (Genesis 24:60)

“Yesimcha Elokim k’Sarah, Rivka, Rachel, V’Leah.”

“May God make you like Sara, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah.”

“Yevarechecha Ad-nai v’yishmerecha, ya-air Ad-nai panav aylecha v’yeechunecha, yeesah Ad-nai panav aylecha v’yahsame lecha shalom.”

“May God bless you and keep you. May God make His face shine upon you and be gracious to you. May God lift His countenance upon you and grant you peace.”

And with this, the groom is off to the chuppah, soon to be followed by the bride to begin the Kiddushin ceremony.

A Modern Take on the Bedeken

For years now and for a variety of reasons, the bedeken ceremony lost favor amongst modern Jewish couples. The veil and a critique of the bride needing to be modest and demure were at the center of this. The idea of a groom “confirming” his bride and veiling her as if possessing her was also not too favorably accepted in spite of its Biblical source. But new interpretations have been applied and a revision of the ceremony in a personally-tailored manner has been responsible for bringing the Bedeken back.

Today in a modern Jewish wedding the tisch and the bride’s reception are probably no longer two separate events. The bride and groom may both give the d’var torah or may not choose to do it at all. Both will be present for the ketubah signing. And the bride, who may well choose to be veil-free or veiled, might put a kipa or a tallit on the groom and then off to the chuppah they go.

Alternative Jewish wedding veil ceremonies have cropped up that capture the spirit and emotion of the traditional bedeken. The veil-free bedeken were, with their eyes closed, both the bride and groom are led into a room and are stood back to back. Blessed by their families (and /or others,) they are invited to turn around and open their eyes in order to see and accept each other for who they really are. Truly a magical moment that encapsulates the very essence of marriage. This can also be a beautiful ceremony for a two-bride wedding, as well.

No Matter if the bedeken is a more traditional ceremony or a reinterpretation of the tradition with a twist, the Jewish veil tradition is steeped in multiple layers of meaning and emotion and a momentous ritual in an evening of extraordinary moments.