Sephardic Wedding Traditions

The Sephardic and Ashkenazic Jews represent the two main divisions of Jewish ethnic groups; with the Sephardic Jews being those who originally dwelled in the Iberian Peninsula and the Ashkenazim, whose origins were in Europe (France, Germany, and parts of Europe). Today, the Mizrachi (Eastern) Jews, despite not being of Spanish/ Portuguese descent are often grouped with the Sephardim since many of their traditions and customs are similar to the Sephardic tradition.

With the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, and shortly then after from Portugal, the Jews migrated to countries where they sought protection from persecution and the freedom to practice as Jews. Most fled to North Africa where they lived under the aegis of the Sultan of Morocco and to the Ottoman Empire. There, they were able to sustain Jewish spiritual life and continued to engage in and expand the rich Sephardic customs and Sephardic traditions that were not to be forsaken. Living in harmony, for the most part, through the centuries alongside their Arab and Berber neighbors, there was a certain amount of cross-pollination of the Muslim and Sephardic cultures.

Today, the Sephardic Jews, dispersed throughout the world, with the largest communities residing in Israel, France, and North America, have retained their distinct and rich Sephardic traditions (minhagim) mixed with cultural influences of the specific geographical regions from which they hailed. The Moroccan Jews and the Persian Jews, for example, share many customs, yet their songs, food, and traditional dress are clearly differentiated by the discrete Moroccan and Persian cultures.

Sephardic Weddings

Nowhere is the richness of the Sephardic customs more apparent (and more widely-embraced) than in the traditional Sephardic Jewish wedding traditions. Although, both Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jewish weddings include the two ceremonies, Erusim (betrothal) and Nisuim (marriage), the minhagim vary quite a bit.

The pre-wedding tradition of the Henna (hina) party is most definitely the favorite of all the Sephardic wedding customs. It is a festive ceremony that, in recent years, has reemerged on the scene. The bride, groom and their guests dress in traditional clothes, exchange gifts, eat traditional foods and dance to the beloved traditional Sephardic songs. The night culminates in the henna ceremony; henna is purported to not only protect the new couple from the evil eye, but will bless them with good fortune, fertility, and happy marriage.

Both the Ashkenazi the Sephardic brides immerse themselves in the mikveh (ritual bath), in a purification ceremony, days preceding the wedding. The Ashkenazi bride will most often be accompanied by her mother or mother-in-law, while the Sephardic bride, after immersion, will celebrate with female family members and friends in Sephardic song, dance, and sweet delicacies.

Traditionally, the Ashkenazi bride and groom fast on their wedding day: a sober reckoning with this momentous rite of passage. The Sephardic view is quite a bit different. The wedding day is viewed as a celebration day or a personal/community holiday; therefore, fasting is not an option. As the Sephardim do not fast, there is no tradition of yichud (separation), where the bride and groom retreat for a short time for some alone time and a bit of refreshment directly following the chuppah. Instead, the newly -married couple at a Sephardic wedding immediately joins their guests to commence with the festivities.

Another tradition that you will not find at a Sephardic wedding is the Bedeken, the veiling ceremony. In the Bedeken, the groom approaches the bride (who he has not seen for a week) and places the veil as to cover her face, right before proceeding to the chuppah. This is not a Sephardic wedding custom. Nor, does the Sephardic bride circle the groom seven times under the chuppah as does her Ashkenazi counterpart.

Furthermore, the tradition of a chuppah with four poles is not a Sephardic wedding tradition. Rather, the Sephardic bride and groom stand together, sheltered under the groom’s wedding tallit (prayer shawl) covering their heads. Historically, Sephardic weddings would take place during the day and not under the stars. Today, very often the Sephardic temple wedding ceremony takes place within the temple’s sanctuary.

On the Sabbath following the wedding, the Sephardic tradition is to have what is called a Shabbat Chatan (the Groom’s Sabbath) The groom is honored by being called up to the Torah (aliyah) to recite a special portion or blessing, and consequently is showered with candies and sweets. The Ashkenazim, on the other hand, celebrate the Shabbat Chatan, known as the Aufruf very similarly, but always on the Sabbath before the wedding.

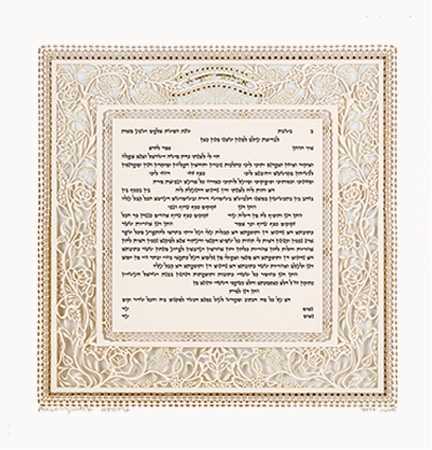

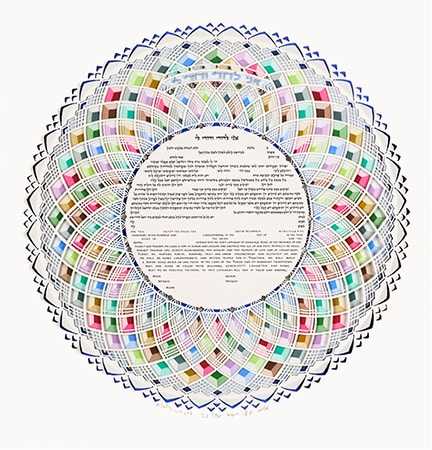

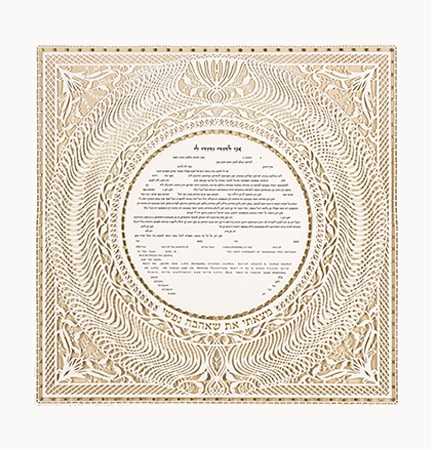

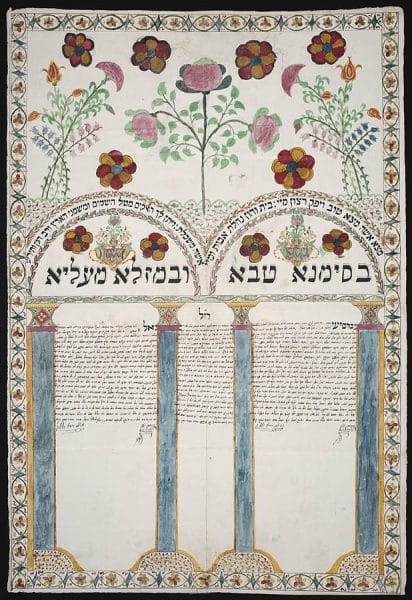

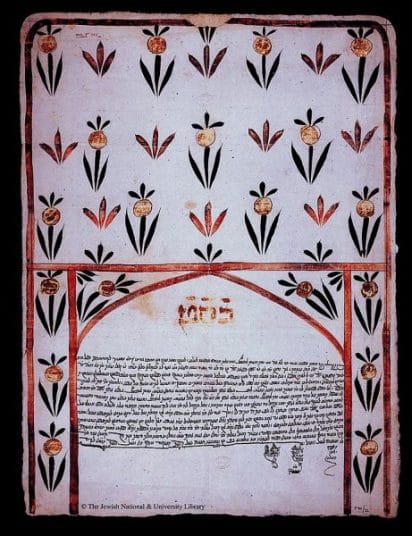

Sephardic Ketubahs

The ketubah history and traditions can be traced to the rabbinic times, dating well over two thousand years ago. Historically, a ketubah, signed by two (male) witnesses, is obligatory for all Jewish weddings and serves/served as a woman’s financial safeguard in her marriage against divorce or the untimely death of her husband.

Historic illuminated Sephardic ketubahs from a plethora of geographical locations provide us not only with an art gallery but also as a sociological history of the lives of the Jews in Spain, Portugal, Morocco, Algeria, Yemen, Turkey, Iraq and more. The artwork shows some influence of locale and culture, but more often, shows the tremendous similarity between these spread-out Jewish communities.

Essentially, traditional Sephardic and Ashkenazic ketubah texts are similar in the language (Aramaic), intent, function, and wording. There are a few differences, however. For example, the Sephardic bride, who has formerly been married, is not differentiated from first-time brides as the Ashkenazim will do by omitting the word mi’d’orata. Very often, the Sephardic ketubah will refer to the bride and groom by recording several generations past and not just their parents. Sometimes, a Sephardic text will elaborate on the bride or groom’s family, if it was particularly illustrious. There is no set sum of money in Sephardic ketubahs as in the Ashkenazi (set at 200 zuzim) This was to be negotiated between the families. And, as well, there are variations in spelling and wording.

Today, the ketubah used in modern weddings has changed quite a bit, reflecting the changes that have transformed Judaism and women’s financial and societal status. The traditional Sepahardic ketubah text is pretty much as it has been for centuries, but there are so many small variations that if you need a Sephardic text it is imperative to get the officiating rabbi’s approval, or alternatively, provide you with one.